Bomb Incidents in Schools:

An Analysis of 2015-2016 School Year

October 2015 – January 2016 Edition

Researched and written by Dr. Amy Klinger and Amanda Klinger, Esq.

Overview and Summary

The vast majority of media reports related to school safety this school year have been about bomb threats. From the high profile reporting of coordinated national bomb threats closing literally thousands of schools in a single day, to the local concerns of an evacuated school, it seems that bomb threats are currently a daily occurrence in schools.

At the Educator’s School Safety Network, we think it is critical to move from mere speculation on this issue to actual facts and data. The Educator’s School Safety Network (ESSN), a national non-profit school safety organization, has compiled the most current information on bomb incidents in America’s schools to determine the scope and severity of the bomb incident problem.

The 2015-2016 school year has seen an unprecedented increase in school-related bomb threat incidents both in the United States and throughout the world. In addition to a dramatic increase in the sheer number of threats, other unique trends have emerged that indicate a need for concern. These include the scope and frequency of the events, the delivery methods of the threats, the perpetrators of these incidents, and the atypical locations of the incidents themselves.

At the same time, school administrators and law enforcement officials find themselves in the untenable position of having to make critical decisions about bomb threat incidents with few established best practices, outdated protocols, and a complete lack of education-based training. More significantly, many school leaders do not understand the potentially catastrophic effects of a bomb incident or do not have the requisite skills to respond appropriately and effectively. It is critical that educational leaders do not abdicate their decision making authority to law enforcement officials or prematurely dismiss bomb threat incidents as a “nuisance”. In fact, many times, law enforcement officials will not make bomb-threat related decisions. It is troubling to note that four explosive devices were found, and one detonation occurred in U.S. schools in the past school year alone. Based on our analysis of bomb threat data and trends, the sobering reality is that an explosive device WILL be detonated in an American school with significant consequences, and we must be ready.

The question that must be considered is not “if” an explosive device will be detonated in a school but rather “when”.

We think it is critical to stop speculating, replying on “expert impressions”, or utilizing outdated information and anecdotes. Instead we must objectively and factually determine the nature, scope and severity of the problem. With this in mind, our report has two important purposes:

1. To provide the educational and law enforcement communities with the most current data and analysis available on the rate, frequency, severity, scope, and nature of bomb incidents in the United States. While components of the report are longitudinal in nature, the primary thrust of the document is to provide an up to date analysis of reported bomb threat incidents in school that have occurred so far in the 2015-2016 academic school year.

2. To provide school and law enforcement responders with an overview and understanding of the critical trends and warning signs that have emerged from our analysis of recent incidents. Because our data collection and analysis is on-going during this school year, issues and concerns are still emerging, however there are recommendations and areas of concern that must be immediately addressed.

Intended Audience

Our report is informational in nature and must not replace appropriate training, but rather should draw attention to the need for it. Educators in particular have not had the benefit of bomb incident or crisis response training, even though the data would indicate that it will most certainly be needed. While school leaders and emergency responders are the primary audience for whom this information is relevant, parents, community members, and other school stakeholders also have a clear interest in the safety and security of their school communities.

Data Collection Methodology

In our research, we were unable to find any current publically accessible national data on bomb threat incidents. This document is built on a data set that is a compilation of bomb incidents that have occurred in U.S. schools as reported from media sources.

During the study period of November 2011 through November 2014, data for the longitudinal component of the study was initially collected from the School Safety News website (formerly www.schoolsafetynews.com). School Safety News was a national organization that in addition to other services, compiled data on specific safety related issues that occurred in U.S. schools based on information reported in the media. These incidents were categorized and/or sorted by the nature of the incident, date, and geographic location. School Safety News data from November 2011 through December of 2014 was used by ESSN researchers to compile a data set consisting of all bomb related incidents occurring at a school during that time period. As of December 2014, this data resource was no longer available. The data set used for analysis of the 2015-2016 school year was compiled directly by our own ESSN researchers in a similar fashion using media sources.

Reports of all bomb incidents in schools were reviewed and data collected on the date, location, type of incident, type of school, how the threat or incident was delivered/discovered, and the response protocol enacted. This data was verified and aggregated to arrive at the findings incorporated in this report. Data collection for the 2015-2016 school year has concluded and the final study results are included in this document. Data collection for the 2016-2017 school year began August 1, 2016. Periodic updates will be issued throughout the upcoming school year.

Limitations of the Study

It is highly unlikely that all bomb-related incidents in schools have been included in the data set. In fact, it is likely that numerous incidents have been either not been reported, or inadvertently missed by the data collection methods used. Rather than undermining the findings, this potential “under-reporting” only seeks to emphasize the significance of the dramatic increases found in the study.

Both data sets (longitudinal and 2015-2016) have similar limitations in that they are based on reports made in local and/or national media. This means that while multiple media reports were used to verify and update the accuracy of information related to an incident, if no information was released by the school or the incident was never reported in any fashion, then it is not included in the data set.

The dates in which schools start and end their academic year variy widely. In an attempt to maintain consistency, data from June, July, and August are not included in the study, as the number of schools in session during those months is inconsistent compared to September through May, when nearly all schools are in session.

Summary of Findings

Is There an Increase in the Number of Bomb Threats?

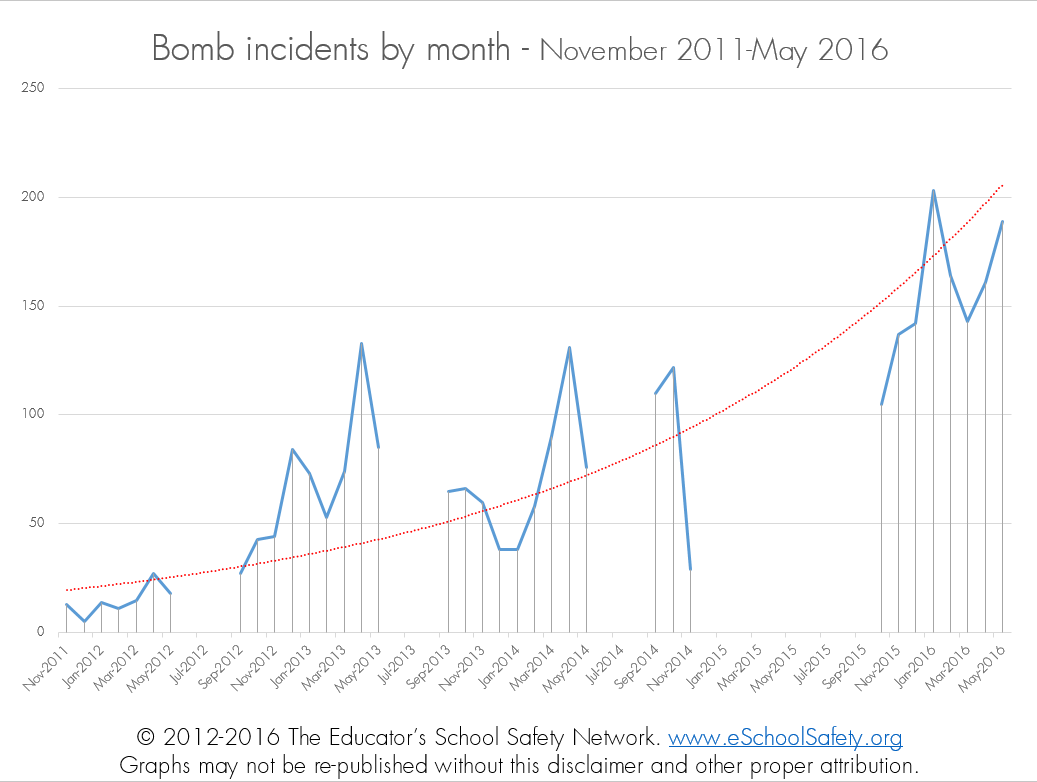

Perhaps the most significant result of the data analysis is the dramatic increase in school-based bomb threat incidents both over the last few years and specifically during the 2015-2016 academic year. While incidents have been gradually increasing since 2012, in the 2015-2016 school year U.S. schools have experienced 1,267 bomb threats, an increase of 106% compared to that same time period in 2012-2013.

This is not just a one-time occurrence: since November of 2011 there has been an increase in bomb incidents of 1,461%.

While this report focuses on United States schools, our data indicates that this is an international phenomena as well, with school-related bomb incidents occurring at an increased rate in virtually every continent in more than 22 different countries this school year alone.

In What Months Do Bomb Threats Occur?

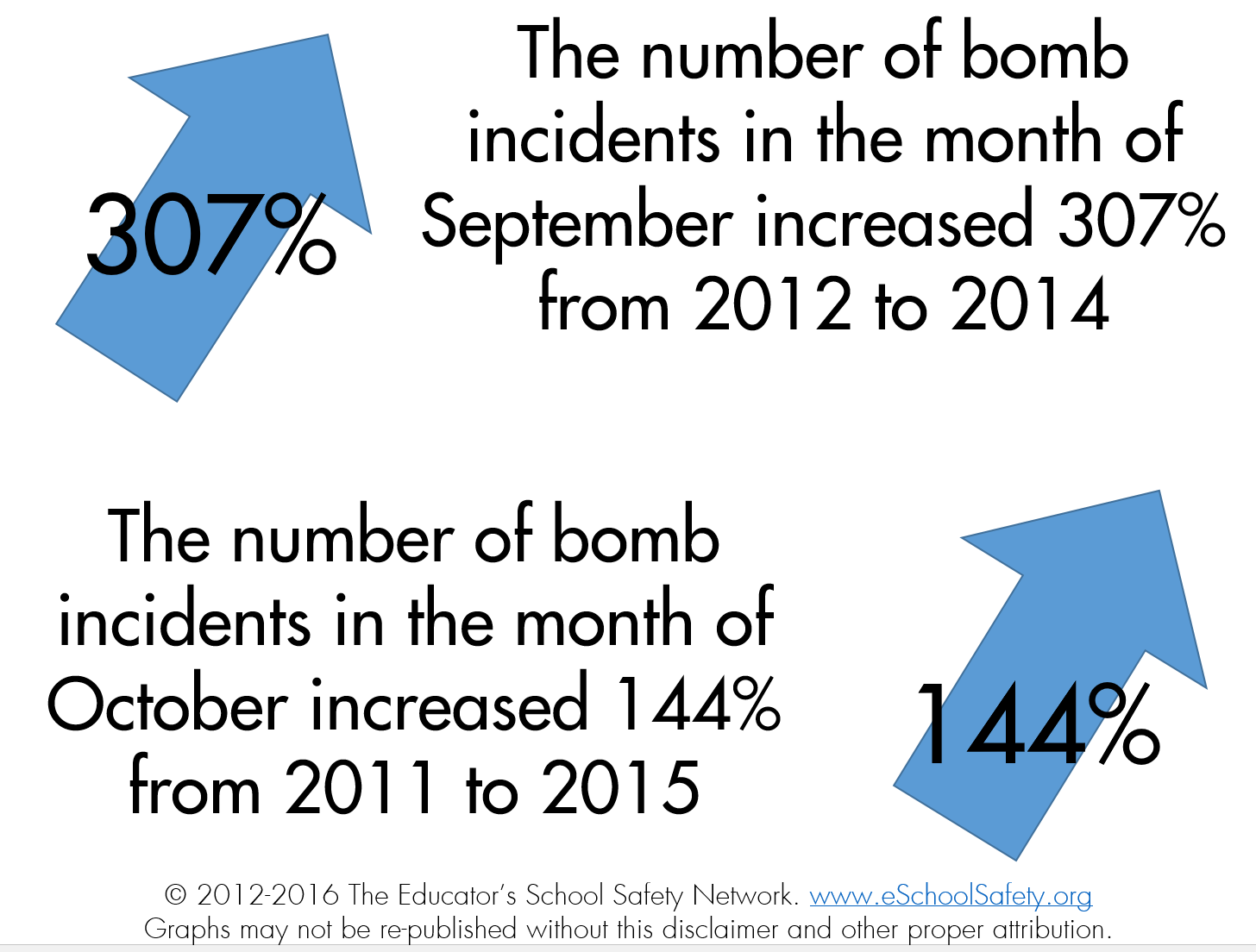

Bomb threats are often incorrectly considered to be more prevalent in the spring as an “end of the year”- type prank. In reality, this is not the case. The number of bomb incidents in schools during September increased 307% from September 2012 to September 2014. October threats increased 144% from 2011 to 2015.

From 2012 to September 2015, the months of April, October, and September had the most bomb threats with an average of 97, 77, and 67 threats respectively. While these months historically had the highest rates of bomb threats, they comprised only a small percentage of threats (April 18%, October 14%, September 13%). Because of the dramatic increase in threats in the spring of 2016, when 2015 - 2016 data is included, April is still the month with the most threats overall (an average 113 per day, 16% of all threats), however May is now second with an average of 92 threats per day and 13% of all threats.

October is third with 84 threats per day on average, comprising 12% of all threats. The rate of bomb incidents is almost equally spread throughout each school month. When examined over time as well as just for the 2015-2016 school year, it appears that bomb threat incidents are a year round concern and occur at a fairly constant rate throughout the school year.

How Many Bomb Threats Have Been Reported?

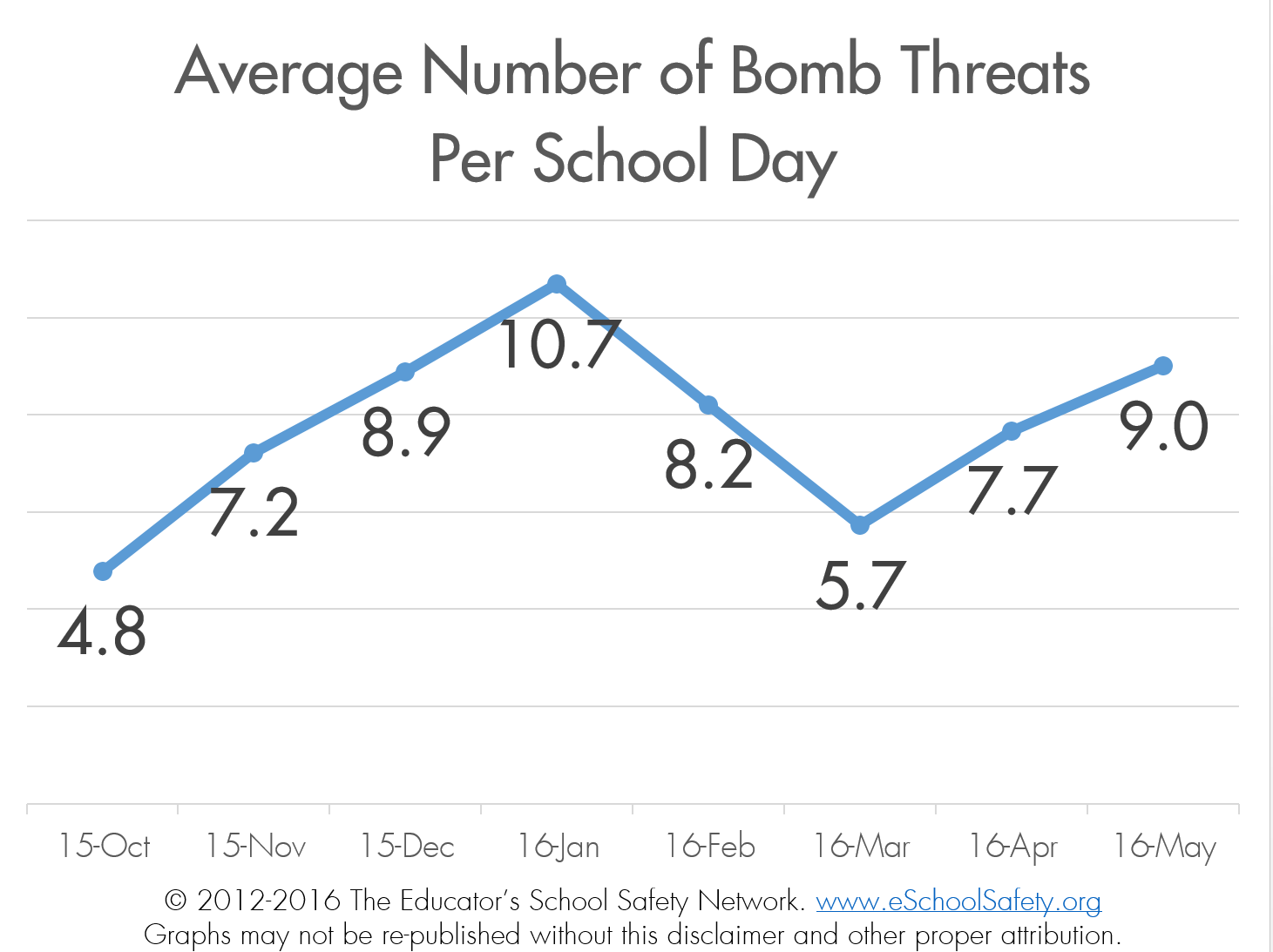

While there is clearly an increase over time in the number of bomb threats in U.S. schools, statistics from this school year alone demonstrate a startling trend. January of 2016 saw 206 school-based bomb incidents, an average of more than 10 threats per school day- the highest number recorded to date. While the rate decreased in March to an overage of 5.7 per day, this may be attributed to a lower number of school days that month due to Easter and/or spring breaks. By May 2016, the rate of bomb threats had risen to 189 incidents, an average of 9 per day.

Which States Have the Most Threats?

Prior to the 2015-2016 school year, California and Ohio reported the most bomb threats during the previous three year period. Widespread instances of threats made through automated calling on the east coast in the second half of the school year has altered this dynamic with Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Maryland now experiencing bomb threats much more frequently. Despite this rapid increase, Ohio, California, Florida, and Pennsylvania consistently have ranked in the top positions for bomb threats in schools, not just this school year, but in the longitudinal study as well. At the conclusion of the 2015-2016 school year, Massachusetts had experienced 10.7% of all bomb incidents, followed by Ohio with 7.6%, and New Jersey with 6.8%.

In the past school year, every U.S. state, and several U.S. territories have experienced at least one bomb incident.

Where Do Bomb Threats Occur?

There is often an assumption that school bomb incidents occur almost exclusively in a secondary school or higher education environment. This may have been true in the past, however our data from the 2015-2016 school year indicates a disturbing trend. While more than a third (35%) of bomb incidents occurred in high schools, more incidents effected schools with much younger students – 20% in middle schools and 44% in elementary or primary schools that include preschool children.

These “non-traditional” targets of bomb incidents contain extremely vulnerable populations and are often ill-equipped and trained to deal with crisis events.

When a specific school was targeted for a bomb incident, it was most often a high school, with 61% of targeted threats. While the rate of threats was lower at 18%, both middle and elementary schools were targeted equally.

In a high school or higher education setting, the perpetrator of the event was often found to be a student who desired the disruption and/or notoriety achieved. At the elementary level, the perpetrator was often someone from outside of the organization whose purposes are much more obscured – and potentially much more deadly.

How are Bomb Threats Made?

As in the past, during this school year, almost half of the bomb threats received were called in to the school itself. There has been much media attention about “swatting”, where an automated call or threat is made via the internet, typically to a significant number of schools at once. An example of this occurred on December 15, 2015 when hundreds of school districts across the United States received automated call threats, resulting in the closure of more than 900 schools in California alone. In just one day, May 23, 2016, there were 68 bomb threats impacting 53 schools in 18 states, more than half of which were elementary buildings.

It is sometimes difficult to determine if the call reported was an automated call or an actual person, as this is often not clearly stated by media reports and/or law enforcement officials. When this distinction was clear, it was almost evenly split. Approximately 50.2% of the time the threat was made by an actual person, with automated calling reported about 49.7% of the time. This is a significant increase in the second half of the year, with automated calling reported only 12.9% of the time in the fall of 2015.

While more than 50% of bomb threats were called into the school, 32% of the time the threat came from within the school itself, most typically as a note or written threat. In more than 71% of those cases, the written threat was found in the restroom. Technology was not a significant factor in bomb threats, with only 10% of the threats delivered by email or some form of social media.

How do Schools Respond?

The nature of a school’s response to a bomb incident is difficult to quantify because (1) it isn’t always reported, and (2) evacuation can mean a brief evacuation from school, dismissal or cancellation of classes – or both. The terminology to describe response protocols is often not consistent as the terms lockdown (typically used in response to violence actually occurring) and shelter in place (used for chemical or biological threats) are often used interchangeably. In many cases there is a mixed response – an evacuation, a search, then classes are cancelled. The nature and scope of the search isn’t typically reported either.

In general, however, evacuation is the most frequently used option – 79% of the time – and this number is most definitely much higher. One critical consideration in the response of schools is the notion of “user fatigue”. When numerous bomb threats are received by the same organization within a short period of time, as is often the case, there is a tendency to discontinue evacuation practices or to become less vigilant in the response procedures themselves. The “boy who cried wolf” mentality is a real threat, and the half-hearted response that results may well be the intent of potential bombers.

Why are so Many Threats Occurring So Close Together?

As evidenced in the data for states with the most bomb threats, there are two other factors at work. Given the close geographic proximity and dates of bomb threat clusters, there is clearly a copycat effect. The initial threat provokes a satisfyingly disruptive response and a good deal of media attention, encouraging others to perpetrate additional threats to achieve similar results. While the reach of those engaged in the “swatting” phenomena discussed earlier in this report is extensive, the desired impact of these incidents is maximized by clustering the events within a specific geographic area over a short period of time. At the same time, the scope of automated call threats allows for multiple disruptions to occur simultaneously across the U.S. and other countries.

Recommendations

While law enforcement officials are almost always involved in responding to a bomb incident, their primary focus is on taking action after a bomb threat incident including investigating, apprehending, and prosecuting perpetrators. School leaders are clearly involved in these same capacities, but also have the additional responsibilities of ensuring the safety of all school stakeholders, responding to the event, and preventing subsequent events.

School administrators need to develop the critical skills necessary to prepare, prevent, and respond to bomb incidents. All building and district administrators should:

- Have a functional understanding of explosive devices, sheltering distances, and the disruptive/destructive capabilities of explosive devices

- Have an understanding of the protocols and practices that will be employed by emergency responders

- Be able to appropriately assess the level and validity of threats

- Be able to identify and analyze pre-attack indicators

- Have protocols in place to prevent future bomb threats and diminish copycat incidents

- Have the capability to conduct appropriate and effective searches of school facilities.

States and/or localities must provide training for bomb incidents that is appropriate not just to the needs of emergency responders but contains specific strategies, skills, and information for school decision makers. Trainings should focus not just on response after a threat has been determined, but also on identifying vulnerabilities and violence and/or threat prevention activities.

At present there are few opportunities nationally for bomb incident-specific training that is appropriate, applicable, or available to educators. There are even few training opportunities where the necessary content and skills are presented from an educational, not just law enforcement perspective.

It is critical for educators and emergency responders to be equally involved in training, prevention, and response as it pertains to violence in schools – particularly in terms of bomb-related incidents. Educators must secure a prominent “seat at the table” and be active, equal partners in preventing and responding to bomb threat incidents.

Media Contacts:

Dr. Amy Klinger, Director of Programs, Amy AT eSchoolSafety DOT org

Amanda Klinger, Director of Operations, Amanda AT eSchoolSafety DOT org